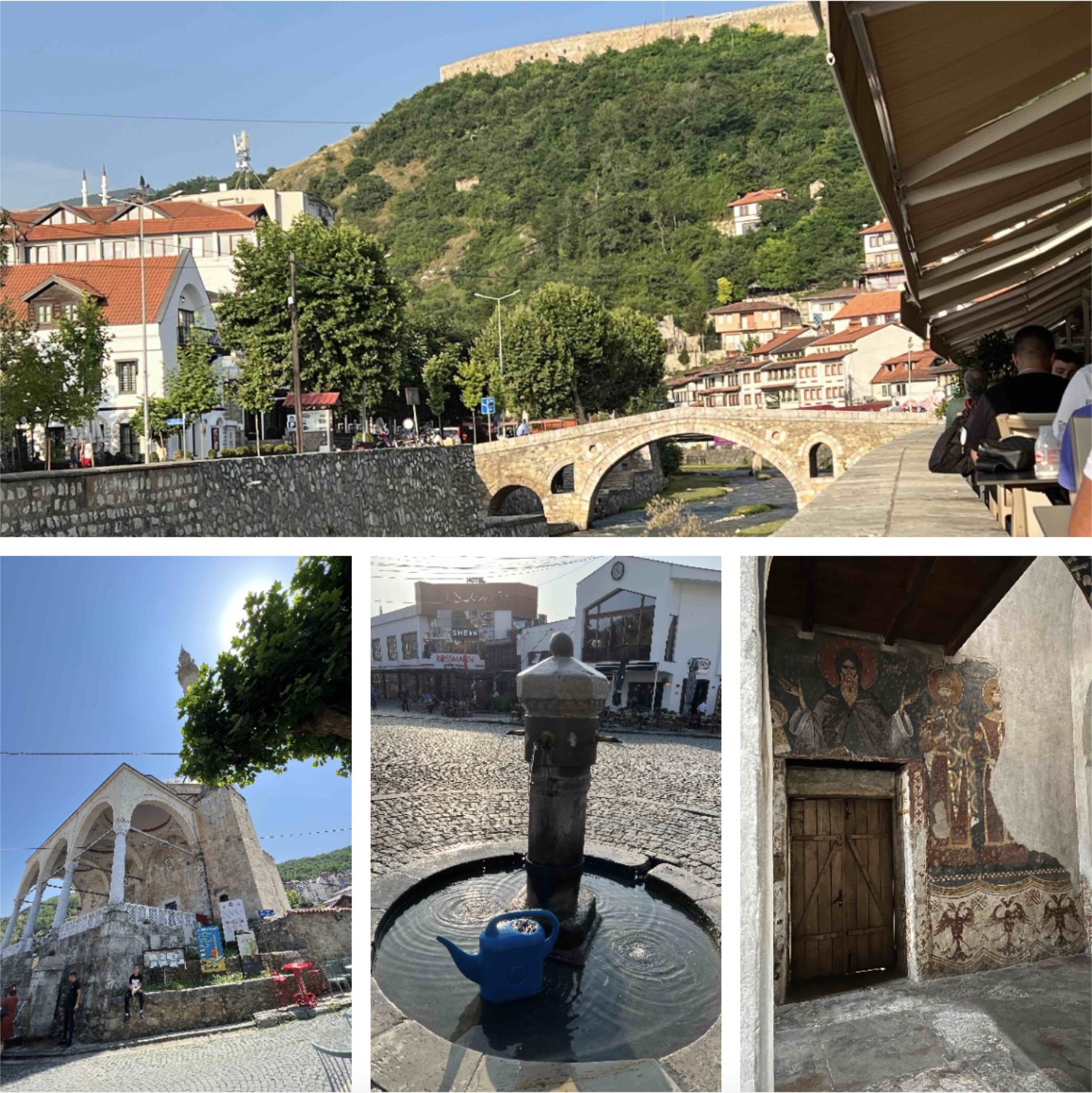

Cover pic: Prizren (by Daniel Ercsey)

I've already written about the beauty of crossing the border, but here the situation is compounded when I have to take out insurance for my car for 15 Euros in Kosovo, which many people think is a non-existent country. But then everything settles down, and there's even a Burger King at the petrol station next to the motorway outside Pristina, much to my daughters' delight. But I don't know what the point of opening such a restaurant in the Balkans is, since they fry the pljeskavica next door and sell it for half the price of frozen beef wrapped in a bun resembling dried camel shit.

Photos: Daniel Ercsey

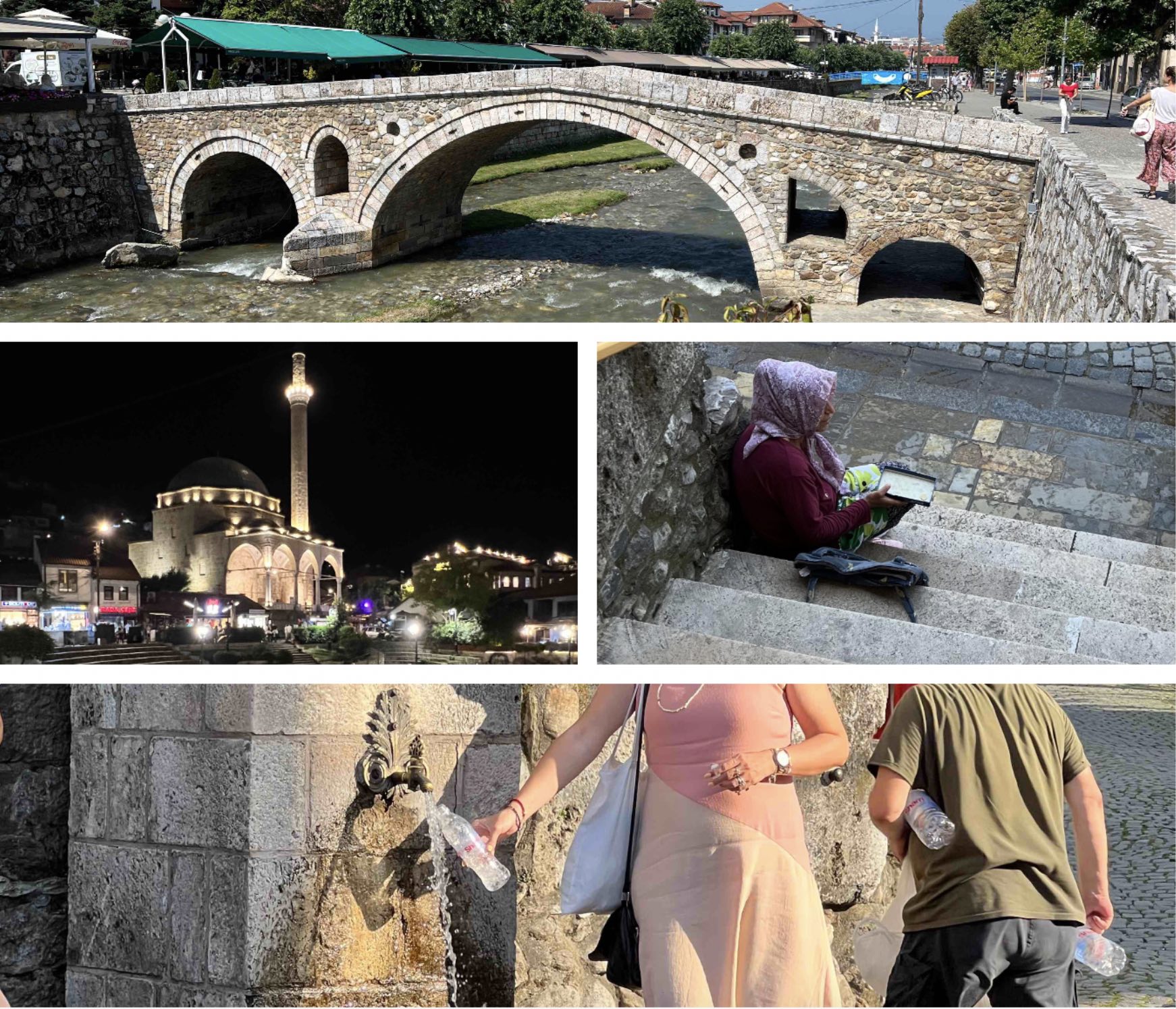

We are heading to Prizren, the southernmost and perhaps most beautiful city in Kosovo, which is the seat of the Serbian Archbishopric and one of the medieval Serbian Orthodox churches (Our Lady of Ljevis) is a World Heritage Site. No wonder, Kosovo is the cradle of Serbian statehood, which gradually became a Muslim/Albanian territory over almost 500 years of Turkish occupation, but the final break-up was delayed by the terrible ethnic cleansing of the Balkan wars on the one hand, and the emerging Yugoslav kingdom and state of which Kosovo became a part. The atrocities committed during the Balkan Wars, mainly against Albanians, have been reported by many, including Trotsky, who wrote of the corpses piled up in the Prizren's castle, and Guinness, who said as much in his speech to the House of Commons (13.02.1913): "Women and children were tied together, doused with petroleum and set on fire, while the men beside them were stripped naked and stabbed to death." The Balkans is a place where nothing is forgotten. When Kosovo declared its independence, the first thing the Albanians of Prizren (who make up 97% of the population) did when they declared independence was to burn down the Serbian Orthodox churches, and it is no wonder that the medieval Serbian churches in Kosovo are still guarded by KFOR soldiers. Modern Prizren is a charming little town with friendly Albanians who do their best to make the visitor feel at home. The waiter teaches you Albanian phrases, the security guard in the shop smiles kindly, and there is no sign of the wave of violence of years ago. It is true, you don't hear much Serbian, it is drowned out by the sound of the muezzins…

Photos: Daniel Ercsey

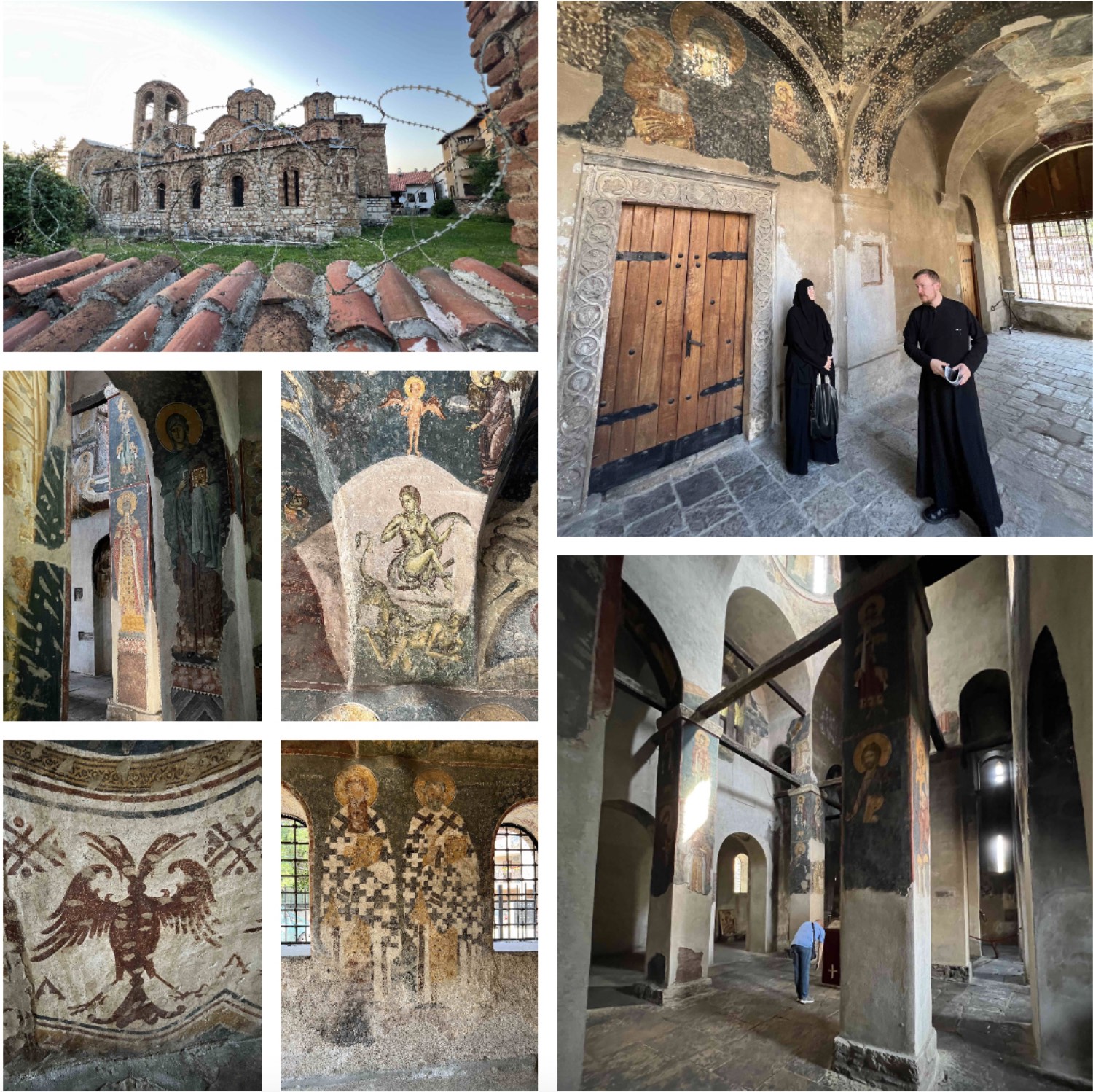

Serbian Orthodox Father Jovan Radic is clearly loved by everyone in Prizren. The young priest is the pastor of the largest church in the centre, dedicated to St George, but now he is giving us an exceptional tour of the Church of Our Lady of Ljevis, which is also protected by UNESCO (since 2006). We meet at St George's Church, and he tells me that he was born nearby, went to high school here, then graduated from the seminary in Belgrade, and got a degree in history from Mitrovica. In the meantime, everyone does greet him, an old woman kisses his hand, a baker offers him fresh bread, which he smiles and refuses. "I understand it's no coincidence that the church is by appointment only!" the young priest's face clouds over. "In 2004, the Albanians burnt down all the Orthodox churches in Prizren and many houses inhabited by Serbs. Before that there were 12,000 Serbs living in the town, now there are only 10. The reason they greet us so warmly is that no one is afraid of a statistical error, and that's all there are now". "But who set fire to these holy places?

"I wouldn't know," he shakes his head, "I'm just a simple priest, not a politician. But I do know that this church, Our Lady of Ljevis, was built before Notre Dame in Paris. When it burned down, the whole world was horrified. When our little churches in Prizren burned, no one even looked here. The world turned its head. And I think it is not only a Serbian heritage, but also important to the world, like, say, the Sinan Pasha mosque next door. Anything that is burnt down in the 21st century is vandalism!

(Father Jovan is right to say that although the Notre Dame in Paris was started 200 years earlier, the church in Prizren was finished earlier. ) The narthex has on its walls the holy kings of the Nemanja dynasty and their flag, or more precisely their coat of arms, the two-headed eagle, which is an ancient Serbian coat of arms, but which seems to be also on the flags of the inhabitants of Prizren today (and I don't mean the flag of Kosovo)…

Photos: Daniel Ercsey

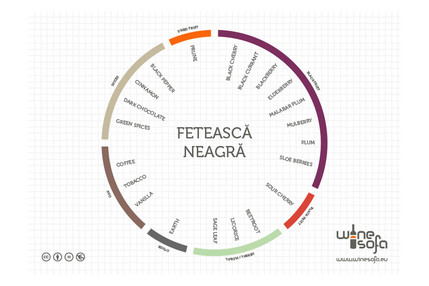

The best Kosovar wine in the BIWC competition is a Vranac, which I end up finding at the local grocery store in the mall on the outskirts of town.

Photo: Daniel Ercsey

Suhareka Verani Theranda Vranac 2017 I 92 points

Deep ruby colour, almost opaque, with a scarlet rim. Nose of black berries, blackberry jam and plum jam, with a hint of black pepper and blueberries. Tasting it, it has a medium to full body, good acidity, the nose repeats the flavour but also adds some black cherry and strawberry. The whole wine has a very ripe impression, yet is not an alcohol monster and the acidity is lively with a long finish. No wonder it has a high rating, 6 years old, yet it still feels fresh.

Photos: Daniel Ercsey

The Sinan Pasha mosque in Prizren, also mentioned by Father Jovan Radic, was built between 1600 and 1608, partly from stones from a nearby Serbian Orthodox monastery. A good example of recycling (assuming that the Serbian monks were not massacred in those days, which I doubt, unfortunately) are the columns and carved pillars built into the interior, also from the former Serbian Orthodox church of the Archangels St Michael and Gabriel. The interior walls of the mosque were painted in the 19th century, mainly with quotations from the Koran and floral ornamentation; here, for example, I saw for the first time in a mosque a depiction of melons, but also perhaps still life. The triple dome in front of the building, supported by columns and which makes the mosque such a dominant landmark, collapsed in an explosion in 1915 (I was unable to find out who blew it up and why) and was only rebuilt in 2011 with the help of the TIKA (Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency). The latter is a perfect example of how Turkey and Erdogan are trying to gain influence in the Balkans, not only in Kosovo, but also in Albania, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Serbia and Bosnia.