Although it may come as a surprise, in recent years, dry Furmint from Tokaj has become very successful.

For many, Tokaj is synonymous with being one of the world’s most wonderful sweet wines. I love these too, because let’s face it, this is not always reflected in the price of the wines. If, in a blind test, we put the world’s most expensive wines into order, in the end there will definitely be several Tokaj Aszú in the first few; if, however, we put the cellar prices into order, you can be sure that these wines will be amongst the last. Just think about it: at the moment, you can buy a high quality, well-balanced, 6 puttonyos Aszú at a small family winery for 10-12,000 forints (sometimes even less), about €32-38. Even Aszú from the most well-known producers doesn’t hit the €100 mark, which considering the way Aszú is produced, is a laughably low price.

Well, I don’t really want to go on about this now, but rather reflect on the dry wines from the wine region. At the beginning of the 2000s, the first such reference wines were born, which indicated that the region was capable of more than just producing simple, basic wines. The development of the vineyards in the last 500 years had already preordained this opportunity and perhaps in the past – before Communism – the winemakers were already doing so, although let’s not forget that in the past, sweet wines commanded the greatest prestige. This is not so surprising if we consider that a hundred years ago, there was far less access to sugar and sweetness than today! I’d just like to say a few words about the vineyards. For laymen, I generally use Burgundy as an example. Of course, it’s difficult to make comparisons, given that a long-established, multi-level system relating to the vineyards has been in existence there for quite some time, but in Tokaj the same system had actually evolved much earlier (in the 1730s, the vineyards were already classified into three growths, depending on quality). Nowadays, the region is divided into more than 400 separate vineyards and an increasing number of winemakers are once again taking into account the results of the sixteen-vineyard classification born in the 18th and the first half of the 19th century.

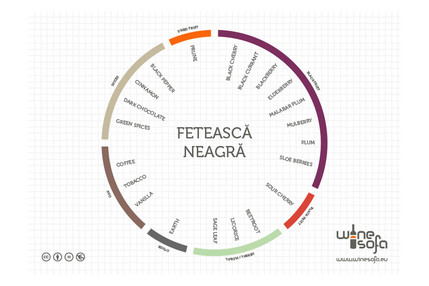

Let’s take a quick look at the grape varieties. The dry Sárgamuskotály (Muscat Lunel), although very pleasant on a hot summer’s day, is never going to set the world on fire. The other two varieties are rather more interesting. Hárslevelű (Lipovina) can make really lovely dry wines. Its floral fragrance perhaps makes these wines easier to understand and the acidity is a little less intense than that of Furmint. If we consider how it matures, thus far it would seem that it ages more smoothly than Furmint, but as yet, there is no evidence that its ageing potential is shorter. Nevertheless, it seems that the majority of winemakers – also taking into account the region’s natural endowments – are backing Furmint, since Furmint is capable of working wonders in this region. Transformed into a dry wine, a decade of ageing presents no problems (we don’t yet know much more about this due to the initial low number of bottles produced), the acidity resulting from the volcanic soils is vibrant and lively, and the majority benefit from maturation in used barrels, although the totally reductive wines from more experimental winemakers are also fantastic.

There are however many questions which will only be answered in the future. On the one hand, Furmint is a variety with a relatively neutral flavour profile, meaning that it can best be compared to Chardonnay, whereas on the other, its acidity is much closer to that of Riesling. First of all, although it may surprise you, these Furmints reminded me of dry Vouvray. Chenin Blanc is anyhow similar to Furmint in many ways, with high sugar levels and relatively high acidity, meaning that the wines can age for up to 30 years. If I consider this analogy, dry Tokaj Furmint should also be capable of something similar (probably, Anthony Hwang also realised this when, in addition to Domaine Huet, he bought the Tarcal Királyudvar winery. It is interesting to compare the dry wines from the two estates and contemplate the relationship between the two.)

In addition to its ageing potential, I should also mention some other aspects of dry Furmint. At the moment, there is not really any kind of uniform style for these wines, although there is some consensus among the majority of producers that Furmint presents best at 13-14% alcohol. At first it may even seem overwhelming, but after tasting several hundred (or perhaps more than a thousand) dry Furmints, I can happily say that these big, dry wines are easily able to ‘withstand’ this level of alcohol, given that they generally have a high dry matter content, are full-bodied and have serious acidity. But what is even more exciting is the world of vineyard-selected dry wines.

The majority of the region is volcanic, mostly determined by post-volcanic activity. In addition to the presence of rhyolite and andesite, the remains of numerous ancient geysers and the silicified and crystalised rocks resulting from the hot water bubbling up long ago make this exciting terroir. The thick cover of loess (found only here in the wine region) on the lonely cone of the visual motif of the region, the Tokaj Hill, must also have arrived here from somewhere. Thus, wines from here are often softer and age more quickly; however, they are more understandable, approachable and easy drinking. The volcanic vineyards are not uniform either; in the last decade, the Mád winemakers have perhaps done the most to ensure that the vineyards belonging to the community are able to reveal themselves through their wines. Of course, the situation here is similar to that in Burgundy. The wines from the old, first-growth lands are more likely to be multi-layered, although a good winemaker from a third-growth area is also capable of making a wine which may surprised those at a blind tasting.

Finally, there is one more basic, but important consideration when buying a dry Tokaj wine: the vintage. Tokaj is situated relatively far north, where the vintage effect is very important. It is simply not possible to produce the same quality in a bad year as in a good vintage. In my view, however, this is no bad thing. The world would be boring if the small amount of wine from my favourite producers were the same every year. Thus, at least every year I can go to the Tokaj wine region and taste all the wines from the producers again and again, I can discover a new winemaker who has created something outstanding and I can talk to those who, for whatever reason, are not having a successful year.

Having read all this, it might just have reinforced the feeling that it’s not worth buying dry Tokaj wine. You need too much information; you need to know about the vineyard area, the grape variety, the vintage, the winemaker and so much more. However, I ask you, how much more complicated is it than Burgundy? Doesn’t the vintage count there? Do no differences exist between the vineyards there? Moreover, buying from Tokaj is still much cheaper than the big-name wine regions. Think of it as a kind of treasure hunt. Believe me, it’s worth it!