Cover pics: True terroir driven wines from Miskolc, Hungary - Photos: Daniel Ercsey

There are countless minor and major fault lines visible in both the Hungarian and international wine markets, but it is encouraging that ideological differences seem much less important than they did a few years ago.

Is this a terroir wine? Hmm... - Photo: Daniel Ercsey

Fifteen years ago, “artisanal” was the buzzword, although even then its users could not agree on what it meant, so the term quickly became meaningless. This was followed by the term “natural,” which suffered the same fate a few years ago, although its rise lasted much longer and had a greater impact than the term “artisanal.” However, the fact that the end result was similar is not due to the participating or opposing wineries, but rather to consumers, who, it seems, were not interested in maintaining a divisive approach in the long run. The majority simply want to drink good wine, with less and less information. Just as the average consumer is not interested in residual sugar, acidity, tannins, or the slope angle of the vineyard, they are not really interested in whether the wine contains gelatin, bentonite derivatives, or sulfur. Of course, there are and always will be those for whom this is a cardinal issue and who will argue until the end of time about who is poisoning whom and with what, but it is safe to say that by 2025, the natural-technology debate will have run its course and the focus will have shifted elsewhere.

Uniqueness delights others (Frescoes in the church of Velemér (Hungary) from 1377) - Photo: Daniel Ercsey

The first technologically important issue that everyone is talking about today is the topic of reduced-alcohol wines. Here, 95% of winemakers feel threatened by the overwhelming market success of NOLO wines, so the former natural wine producers have joined forces with the winemakers who have always been in the majority, who did not imagine the future of winemaking without sulfur, but at least with alcohol. The second problem—let's call it that—is the rapid spread of Flavescence dorée in Europe, which ultimately brought together everyone involved in grapes and wine on the old continent. It is an old cliché that a common enemy helps to overcome internal divisions, but this time it proved to be true. Coordinated defense, joint spraying, and systematic monitoring are being organized across Europe, and abandoning vineyards is subject to sanctions, as neglected plantations are breeding grounds for the disease. From this perspective, it does not matter whether you are an investor farming thousands of hectares, engaged in large-scale cultivation and wine production, or a small, artisanal winery with three barrique barrels; it is in everyone's fundamental interest to keep their vineyards free of infection.

Some people will be presenting a dry yellow muscat from 2004 in 2025. (Géza Lenkey) - Photo: Daniel Ercsey

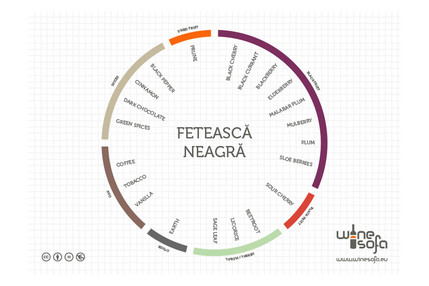

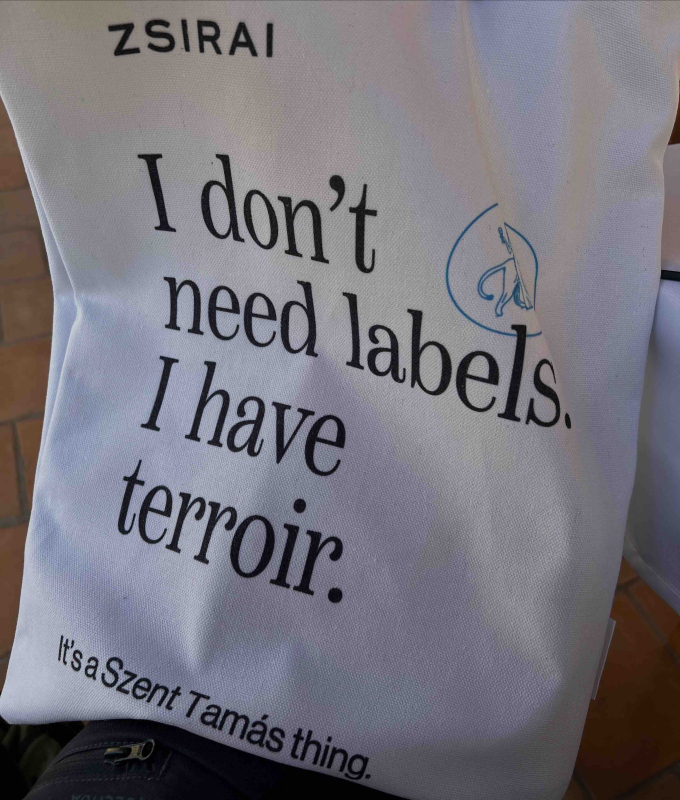

If we absolutely want to find an existing or re-emerging front line in 2025—which, incidentally, is nowhere near as sharp as anything else in the industry over the past decade—then it is perhaps visible between the trend followers and the trend setters, the wineries that never follow trends. Of course, there are many things that fall under this umbrella term. Some people reject any kind of trend, even those they themselves may have created, and from there it is only a short step to criticism of consumer culture, the erosion of the sacredness of wine, the rise of pop culture, and the apparent democracy of opinions, which claims that everyone's opinion is equally important, suggesting that ultimately it is the consumer, i.e., the market and money, that decides what is valuable and what is not. This view ignores the historical experience that, while ultimately it is always the market that decides, this traditionally happens as a result of the decisions of opinion leaders and critics. Picasso would have been nowhere if his mentors had not embraced him, as it is clear that even today, 90% of his admirers do not understand a single one of his works, but simply believe that what they see is great, and the price only reinforces this belief. The Picassos of today's wine world are undoubtedly the winemakers who work with a terroirist approach, who want to see the vibrations of the given vintage, the soil, the microclimate, and the bedrock reflected in the wine. Some believe that this is evident in full maturity, some swear by low alcohol content and sparkling yeast (which is known to give one of the most neutral flavors), others prefer spontaneous fermentation, and still others—to bring in the natural line—produce wines according to the "I don't add anything, I don't take anything away" principle, but their primary goal is to showcase the terroir and, ultimately, uniqueness. And with that, after a lengthy introduction, we arrive at the real key question. Ninety-eight percent of the wines available on the world market, even if technologically flawless (including Georgian orange wines), have no unique character whatsoever. This does not mean that they are not delicious, drinkable, or that they cannot have silky tannins or a long finish. These mass-produced wines, in both the good and bad sense, can easily score 90+ points in wine competitions or magazine tests. In fact, it is mostly these wines that receive such scores, simply because of the law of large numbers. The remaining 2%, however, thanks to the terroir, have unique characteristics that make them recognizable in the sea of wines.

That says it all. (Tokaj wine region, village of Mád, Szent Tamás vineyard) - Photo: Daniel Ercsey

Make no mistake, this is not a statement about quality. What is recognizable is not necessarily better or worse than the rest, and in many cases, the average consumer may think of these wines as bizarre, difficult to understand, and inaccessible. This is where the importance of education comes into play. If we want people to understand these wines, we have to take them by the hand, take them to the region where they are produced, and act as intermediaries between the wine region and consumers. Of course, there is another way, which at first glance seems much easier. We have to make wines that don't require any thought, wines that the market wants. From a purely market perspective, this is the key to survival, the only solution. The only thing that will be lost is precisely what made people fall in love with wine and dream of it as the blood of Christ. Its inimitable uniqueness. Everything else, from fermentation to tutti-frutti flavors to sparkling labels, will remain. Yet it will not be the same.